Written, designed and photographed by local people this hard back book tells the story of Ham and Petersham and its people.

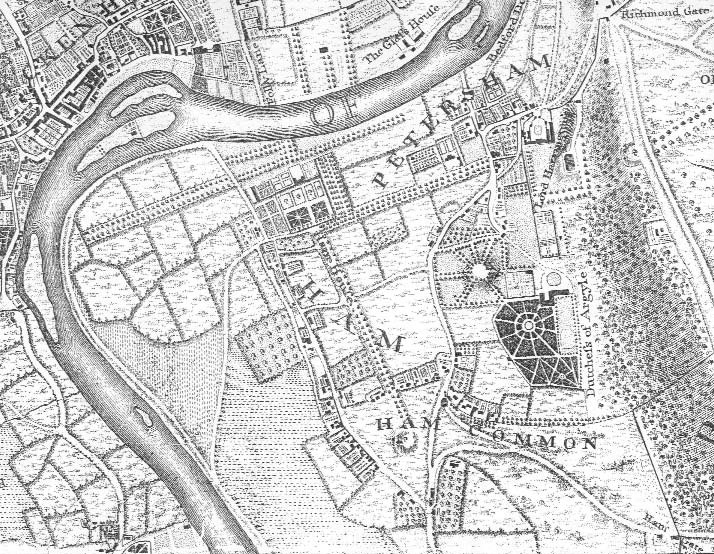

John Rocque’s map of Ham and Petersham c.1746

Reproduced by kind permission of the Local Studies Library, Richmond

Introduction:

Ham and Petersham are a neighbouring pair of ancient villages on the south bank of the river Thames which,to a remarkable extent, have managed to preserve their village status and historical character in spite of the developmental pressures of the 19th and 20th centuries. The aim of this book is to celebrate what makes the two villages so special and of such interest by bringing together a selection of the available relevant historical material both in words and in pictures. It pays particular attention to the buildings and the people who lived and worked in them, but does not aim to be comprehensive; often only an outline can be given if the account is to remain within reasonable bounds.

The village of Petersham was recorded in the Domesday Book of 1086 as Patricesham, on land owned by Chertsey Abbey. The survey mentions a church, which would have been St Peter’s, and a fishery ‘worth 1,000 eels and 1,000 lampreys’. It is thought the village of Ham derived its name from Hamme, an old English word meaning meadowland in a bend of a river. It was a hamlet of Kingston, and until 1897 was known as Ham with Hatch.

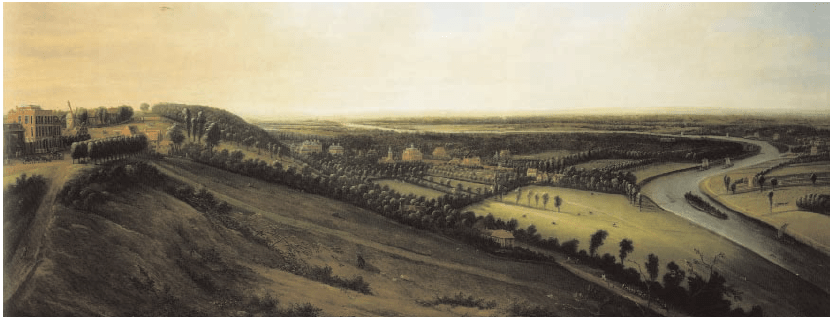

View from Richmond Hill towards Ham and Petersham c.1720 by Leonard Knyff. At 77 x 183 cm it is one of the largest panoramas ever to be painted in England

Originally, Ham was the village along Ham Street and the land to the west of it in the river bend, together with a large part of what is now Richmond Park stretching east as far as the Robin Hood Gate. Hatch was a small area on the north side of Ham Common (the open part of which was at one time called Hatch Green). Hatch was a part of the Manor of Kingston Canbury which had belonged to Merton Priory, and did not come into the same ownership as Ham until the Canbury manor was bought by Wilbraham Tollemache, 6th Earl of Dysart, in the late 18th century. The manor of Ham, originally part of Kingston, was purchased by King Henry V in 1415. At the same time he acquired Petersham manor from Chertsey Abbey in exchange for lands elsewhere.

In the 15th and 16th centuries Ham and Petersham were royal manors leased to the Cole family (see page 78). In the 17th century the lease passed to William Murray, 1st Earl of Dysart, of Ham House, and in 1671 the Duke of Lauderdale, who had married William’s daughter Elizabeth Murray as her second husband, secured the lands of Ham and Petersham in freehold for the Lord of the Manor from the Crown.

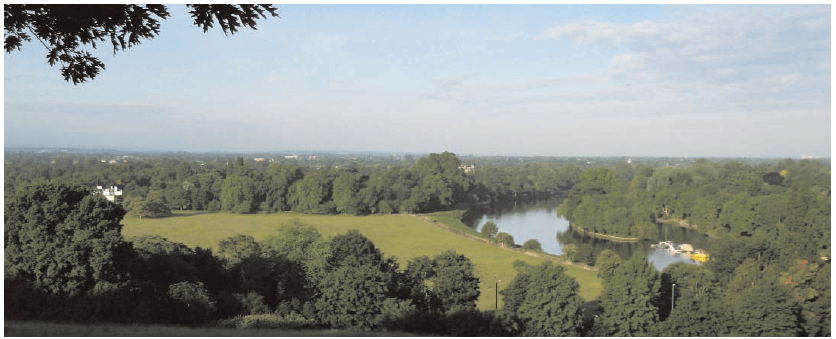

The same view today

Charles I’s determination to enclose Richmond New Park in 1637 faced some considerable opposition, not only from his advisors but also from the landowners whose lands were affected. Traditional rights of way would be blocked to ordinary citizens, and the further taxes that would be required to fund New Park would make the King even more unpopular than he already was. Despite this opposition Charles was determined to press ahead with a hunting park for his private use. A number of neighbouring landowners around the Park were prevailed upon to part with their land, and the terms were generous. Both private and common land in Ham (895 acres) and, to a lesser extent, in Petersham (306 acres) were enclosed to form the Park. In return Charles entered into a Deed of Gift in 1635, granting £4,000 to the two villages and the commons not enclosed to the inhabitants in perpetuity. As commoners they had rights to graze and water their livestock and collect firewood. Charles built nearly ten miles of high wall around the perimeter of the 2,500 acres of his Great Park. Perhaps we should be grateful to the King; without his initiative much of the open space both on the Common and within the Park would by now have been claimed for development.”